- Home

- Justin Rose

Ariel's Tear Page 2

Ariel's Tear Read online

Page 2

Hefthon threw his brush at Geuel in mock anger. He was a blonde, burly youth, large at nineteen and still growing, with thick, heavy features and a wide, simple face. “Better suited! I only learned it from you. Mother says that you and deception are like mermaids and water. The first would die without the second, and the second would lose its charm without the first.”

Geuel shook his head. “How far did you ride, really? You’ve been gone all day.”

“To the edge of the blue hills—but no farther. I was careful.”

“You know better, Hefthon. There have been sightings,” Geuel said, unsurprised but angry.

“I just wanted her to see the City of Youth, just once while she’s still of age. Father showed us both when we were younger. And besides, Daris saw one goblin. That’s hardly sightings.”

“There’s never only one,” Geuel replied. “Risk your life for a sight-seeing trip if you want, but don’t risk your sister’s. Are we clear?”

Hefthon nodded. “Yes.”

“Good, then I guess Father needn’t hear of this.”

* * *

Reheuel sat beside his wife in his study, softly stroking her back and whispering in low tones, “The Emperor has recalled another unit of guards from each of the inner cities. I’ll have to send Hadrid and his men out soon.”

“But you’re already stretched so thin,” Tressa replied.

“I know that, and you know that. But what does that mean to a ruler a thousand miles away? He only cares for his borders. The Empire is expanding—rapidly. Through conquest and truce alike. Before long, all the civilized lands in Rehavan will lie in the shadow of the Golden Iris. With such gains at the borders, what do towns like Gath Odrenoch matter? He hardly thinks of the dangers still within his realm.”

“And the goblins?”

“We don’t even know if the rumors are true. As far as the scouts can tell, only six or seven have left the mountain.”

“I wish we would have killed them when we had the chance,” Tressa said, “when our forces were still full.”

Reheuel sighed. “Yes, that’s what we say now, but we were sick of fighting.”

“I just pray that they don’t come here,” Tressa whispered.

“So do I, Love. So do I.”

Tressa lifted her head from his chest and smiled. “Love—after twenty-two years of marriage, the word still thrills me.”

He smiled at her. “Has it been that long? You still look like the bashful maiden of eighteen who swore to be mine.”

“And you still look like the confident guardsman who wooed me with songs in the evenings.”

“Where does time go?” Reheuel asked, staring at his calloused, beaten hand as it flit across his wife’s shoulders.

“It goes to our hearts, Love. Our hearts eat time, and they turn it to memories. Time never returns because it’s already used up.”

They sat still for a while longer, lost in silent remembrance, thumbing idly through the great volumes of their memories, prying the covers of dusty books and pulling apart pages that had become stuck and stiff through disuse and time.

It seemed to Reheuel, as he sat there, that his wife fed his mind, that her presence cleared his thoughts. The silence and her presence together drove his mind back through memories which had remained untouched for many years. Little glimmers flashed in his focus, special moments which used to be precious but, long since, had faded into obscurity. Little smiles that had flitted over his wife’s lips, occasional glints of light in her hair, words spoken in the stillness of a summer evening—all these things rushed over him. He remembered moments which he had sworn never to forget—and had forgotten. He remembered moments that he had striven to burn out of his mind—but never had. It was all there for the reading—his life. Fifty years. All he had to do was turn the pages.

Darkness crept over the old farm that night, sweeping away the sounds and sights of daylight and giving way to its own nocturnal symphonies: crickets sang in the marshes, an owl questioned the night, and a band of coyotes yapped in the forest, scrapping over some minor prize. Geuel and Hefthon sat in the living room, their voices rising and falling to the flicker of dim candles melting on the table.

“It was stupid. You should never have left alone. Think of Veil. She’s a child,” Geuel said.

“I know she’s a child. That’s why I took her,” Hefthon replied. “Do you remember what it felt like—to see the Fairy City as a child? There was a moment, a moment when your heart stopped beating and a shudder rippled through your blood, screaming that you were alive and that the world was still beautiful.”

“Yes, I loved that trip,” Geuel replied, “and I remember the thrill—but you can’t endanger your sister’s life for a thrill.”

“Thrill! You call it a simple thrill? I saw the city today, brother. I saw it as a man, and all I saw were buildings. I saw tear-shaped buildings that glinted in the sun. Oh, it was still beautiful . . . But it was only beautiful. The magic was gone. Veil saw more than beauty. Where I saw buildings shining in sunlight, she saw the glint of innocence and the spark of youth.”

“It’s just a place,” Geuel replied, “just a part of the world.”

“Does that make it any less fantastic?” Hefthon replied. “Even dreams are part of this world. But the Fairy City is more than just a place. It’s immortal childhood, a place where innocence and wonder never die. To be a child and to see eternal youth, the opportunity only lasts so long. I wanted her to have that while she still could. She’s growing: soon the Fairy City won’t matter.”

Geuel sighed. “I know it’s important to you. Just don’t ride beyond the farmland anymore. I’ve heard things—in town. It’s not safe out there.”

“Fine, it won’t happen again.”

They blew out the candles and returned to their rooms in silence.

* * *

Dawn broke over Gath Odrenoch the following morning, and across the countryside men dragged themselves free from the loving arms of sleep, leaving her for the cold of life. Over the foothills, in the mountains of Gath, goblin laborers laid down their tools and crept back to their dark caverns, replacing man in sleep’s fickle embrace.

Reheuel rose from his bed lightly, gently smoothing the blankets back over the form of his sleeping wife. He walked to the window and inhaled, swelling his muscled chest and basking in the morning chill. When he reached the kitchen a few minutes later, he found his children preparing a meal. They paused as he walked to his chair and then resumed.

Sitting down, he turned to Geuel. “We need to repair the fence in the southern pasture this morning, before I head into the city.”

Geuel nodded. “Yes, Sir. I’ll prepare some planks.”

A few hours later, Geuel and his father stood along the wooden fence line in the southern field of their farm, Geuel digging at the base of a snapped post, trying to pry it from the clinging earth. Reheuel sat across from him, widening the slots in a new post with his hunting knife. He was already dressed in his uniform, the folds of his cerulean robe spread out over the field grass around him. “So, Geuel,” he asked, “how have your fencing instructions progressed?”

“Quite well,” Geuel responded with a grunt, his arms straining as he edged the post up its first inch. “Master Kezeik says I should be able to test next month.”

His father nodded with a light smile on his lips, glancing up only briefly from his work. “Excellent, you shall be an officer one day if you continue as you have. And your archery?”

Geuel released the shovel and responded as he dug his hands down into the earth around the post, seeking a hold. “Not so well, I’m afraid. Master Deni tells me that if I were a hunter I would do best to dig a grave with my bow.”

His father laughed. “That’s just Deni’s way. I expect you to focus more on archery though. We must be versatile. Specialization is a luxury that the guards can no longer afford.”

“Yes, Sir,” Geuel replied. He waited a few seconds to see if his father w

ould continue, then asked, “Will there be fighting soon?”

“Someone has been listening to barracks-room gossip,” Reheuel replied, standing and lifting the new post. “We don’t know. We know that the goblins have been venturing farther afield, getting bold. Several farmers have reported vandalized fences and missing cattle. But, as far as actual war goes, no one knows. We haven’t had a conflict with the creatures in decades. I was younger than you the last time they attacked. Who knows how many are even left up there.”

“Would we win—if there were a war I mean?” Geuel asked.

“I’m confident we could defeat them,” his father replied, “but win? I’d hardly call it victory. We would leave blood and bodies on the field, neither of which we can afford right now. The Emperor is still calling for conscripts, and we’re running out of soldiers. No one would win.”

Geuel tossed aside the stump of the old post and waited for his father to slide the new one into place. “I guess we should hope for peace then,” he said.

“Always,” his father replied.

Chapter 2

Four months passed, and rumors settled. Nervous hearts beat slower. As summer reached its peak, Gath Odrenoch returned to its sleepy routine.

Reheuel lay on the crest of a hill, his head resting on his saddle. It was his second day of travel, and it felt good to just lie still for a bit. Around him, the wild bluebarrels, namesakes of the Blue Hills, blossomed and trembled in the breeze, their beautiful barrel traps trembling enticingly for passing butterflies and other prey.

Staring off at the horizon, Reheuel could just spy the hazy outline of the Fairy City. “The City of Youth,” he whispered as he let his eyes trace the tear-shaped buildings that hung, dribbling along the horizon across the lazy river Faeja. “Amazing, isn’t it, that a sign of grief should represent the innocent race?”

Standing nearby, Geuel nodded. “We all know about the symbol, Father.”

“Tell me about the Tear, Daddy. I want to hear,” Veil cried.

Reheuel leaned back and gazed at the sky, letting his voice sink into a rhythmic tone of narrative, delighted to tell a favorite tale. “Once upon a time, in the earliest days of creation, when the magic cyntras of the Passions and the Traits still flowed through all of creation, man lived in little villages along the banks of the Faeja. And in just such a village there was born a girl named Ariel. She was a perfect child, more beautiful and pure than any other creature. They say that the birds went silent when she sang and covered their faces in the plumage of their wings when she passed.

“Ariel grew and developed in perfect tune with Innocence, absorbing the cyntras of that great Trait. And for many years it seemed that she would never be corrupted. One day, though, when Ariel was no older than you, Veil, she discovered grief. Her father was murdered by bandits in the forest.

“Terrified and alone, Ariel ran away and hid in the rushes of the Faeja. And there she wept. And in her tears, all of her innocence flowed out, expelled by hate and grief. The tears, though, still held the cyntras of Ariel’s innocence. And they pooled and collected in the water, hardening into the gem we call Ariel’s Tear.

“The gem was so full of Innocence’s power that when Ariel lifted it, it transformed her into a new being, a beautiful fairy. And since that time, the Tear has ever remained Ariel’s symbol, the symbol of the Fairy Queen.”

Hefthon grinned. “I can’t believe we’re actually going to visit. It’s been so long.”

Veil, who had paused to pick a bunch of bluebarrels, glanced up at her father. “Do you know Ariel?” she asked.

“I suppose, as much as any man knows a fairy. I’ve visited her city many times, and we speak. I give her news of the Empire.”

Veil’s eyes sparkled. “Can children still become fairies?” she asked.

“Yes, my dear. Every so often in this world, a child is born who doesn’t quite belong, a child too simple to survive its grief. Ariel takes those children and changes them, giving them eternal youth. That’s where fairies come from.”

“I want to be a fairy!” Veil cried.

Reheuel chuckled. “I’m sure you do. But I’m afraid you have too much of your mother’s mind and your father’s spirit for that. Some day you will be blessed to raise a family or to labor in some other way, to give back to your world.”

Veil wrinkled her nose in disgust. “That’s old! I want to be young. I don’t want to get wrinkly and tired and droopy.”

Reheuel laughed. “Are you calling me wrinkly and droopy?”

Veil giggled, sensing her father’s playful mood. “Yep, daddy’s old, like Kezeik’s hound.”

Reheuel rolled over and faced his daughter, staring up at her with wide eyes and drooping lids, imitating Kezeik’s endearingly hideous pet. His daughter responded with gales of laughter before grabbing his hand and saying with sudden urgency, “Hurry, Daddy! We’re all rested. Let’s keep going.”

As he rode beside his father a few minutes later, Geuel asked, “Why are we going to the Fairy City, Father?”

“This world was given wonders for a reason,” Reheuel replied. “They remind us that life is more than dull, drab pain. I want to give Veil something beautiful before reality dashes her illusions.”

“And the human empire has no wonders?” Geuel asked. “How can the world be dull when we stand beneath the fluttering Golden Iris?”

Reheuel smiled. “You’re proud of Gath Odrenoch? Of its people?”

“I would die for my city. It is a mark of human virility and endurance. We carved Gath Odrenoch from the face of a mountain, raised it in the heart of the wilderness. It is a symbol of man’s power—like the Iris itself.”

“And what if one day the Iris is not so noble? Our human Empire is complex, subject to the whims of its rulers. The Fairy City is simple. Immortal childhood, immortal innocence. It is a wonder that will never corrupt.”

“The Iris stands for ideals, not men,” Geuel replied. “I would take pride in it even if all humanity were evil.”

“Then cling to your pride, son. Never let it go. But—not all will share it. I lost my faith in the Iris when the ego of its ruler drove him to conquer rather than protect. I no longer look to the Iris’s ideals. I look to the beauty I find in the world.”

Hefthon, who rode just behind Geuel, said then, “I would say that the ideals of the Iris are not always reflected by the actions of its leaders. Perhaps loyalty to the Iris allows for distaste toward its government.”

Geuel laughed. “My thoughts exactly, little brother.”

Late that night, the family stopped to rest in a stand of pine, spreading their canvas tents beneath a thick canopy of boughs. Reheuel lay in his tent beside Tressa, whispering quietly as they listened to the children in the other tent. “They sound happy.”

Tressa smiled, her glinting teeth the only thing visible in the tent. “I only hope that Veil can still see the city as a child.”

“She can,” he replied. “She’s never known grief or pain. The Fairy City was made for those like her.”

“How far is it?” Tressa asked, shifting herself closer and hunching her shoulders against the cold night air.

“Less than two days. It’s a little under a four day ride.”

“Good. As much as I love riding, I’m starting to miss my bed.”

Reheuel laughed. “You’re getting old, my love. There was a time when a simple journey like this would hardly have affected you.”

Tressa smacked him. He laughed.

“Old? I married a man ten years my senior, and yet he calls me old. What I would not give, my Love, just to stop the world right here, to halt the clock and slip into eternity as we are now.”

“A tempting thought,” Reheuel said.

“Can you imagine it? To live as timeless and changeless as the Fairy City, the two of us like this with our children forever? Why must things change?”

“Because change brought us to where we are,” Reheuel replied as he twirled her hair in his fing

ers, “because change gave us what we have now.”

A twig snapped outside the tent, and Reheuel froze. He clamped his hand gently over his wife’s mouth and watched through the crack of the tent flap. A harsh, guttural huff sounded beside the fire. He reached for his sword. “Stay here,” he whispered as he rose.

Reheuel flung back the flap of his tent and leapt into the open. The light from his family’s smoldering fire cast dim shadows across the camp site. A creature stood in the glow, green eyes glittering in the light. It was a small goblin, about four and a half feet tall, lithe and gangly like all its kind. Its freakishly long limbs bulged with sinewy, narrow muscles that seemed ready to burst through its tightly stretched skin. Its massive, flat nose steamed as it breathed in the darkness, and its long, spindly fingers clutched a sickle-shaped sword.

Reheuel yelled and swung his broadsword, arcing the blade at a downward angle toward the creature’s neck. It dropped to all fours and sprinted for the trees, nickering in a series of eerie clicks. It leapt for a branch and swung into the pine trees, using the weight of its body like the head of a flail on the end of its slender limbs. Reheuel ran to the tents to check on his children. When he reached them, Hefthon was stumbling from the door, his spear clutched in his hands. Geuel stood at the other end of the tent, his sword low and ready. Veil sat in a ball in the middle, her blankets drawn over her head in fear.

“How many?” Geuel asked, his eyes flickering over the tree line.

“Only saw the one,” Reheuel replied. “Probably drawn to the fire.”

“What do we do?” Hefthon asked, his voice quavering with nerves and adrenaline.

Reheuel put up his sword. “Come out, Tressa,” he called. “It’s gone.” He turned to his sons. “We’re closer to the Fairy City than to home. We’ll keep riding.”

Geuel nodded. “Hefthon, help me with the tent,” he said. “Veil, gather the blankets.”

Veil nodded. Wide-eyed, she began rolling up her blanket. Tressa embraced her and whispered assurance.

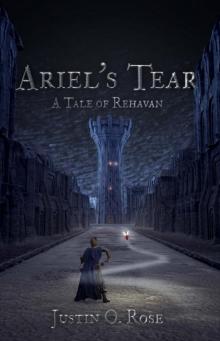

Ariel's Tear

Ariel's Tear